The Mail on Sunday heralded the work as 'Timely and admirable ... her essential idea is that old age should be a stage of life as full of potential as any other'. The Glasgow Herald said it was 'An exceedingly tender, wise book'. Some online reviewers were less flattering: 'I work in a Hospice, so I know all about death and dying, not only in old age. This book uses far too many quotations and passages gleaned from other writers works on the subject of old age and approaching old age. There is no epiphany, no true inspiration. It was depressing and dire...'.

|

| Marie de Hennezel - French advocate for fresh thinking on ageing |

The subject of ageing and death does stir the emotions and in differing ways it seems. I did find the book worth reading; the subject matter is - to make an obvious point - of existential importance. De Hennezel's concern to highlight the transforming possibilities in growing older and understanding how best to approach death is admirable. Yet the way the book is written - its style - grates at times. Too often the pages become a scrapbook collection of sayings - usually wise - about ageing and dying, cut and pasted from books in French written in the first decade of this century. All interesting and usually admirable but it is not always easy to follow the path that has taken de Hennezel, the experienced clinical psychologist, to her present viewpoint.

Marie de Hennezel is two years older than me so she was born in 1946 and is now 78, making her 62 when this book of hers was first published in 2008. She graduated in English and then returned to higher education to eventually graduate as a clinical psychologist with a Masters in Psychoanalysis in 1975. For around a decade she worked as a clinical psychologist in the field of social welfare. Her career was given an interesting new dimension through her brother's role as the chief of protocol at the Elysee palace. He

introduced her in 1984 to President Mitterrand whom she met regularly during the last twelve years of his life. In 2016 she published a book which outlines Mitterrand's inner worlds, a work based on what he revealed to her during those twelve years of his old age.

|

| An ageing Mitterrand |

|

| An irresistible quotation from the wisdom of Francois Mitterrand |

In 1987 she joined the first palliative care unit created in France. Mitterrand had been instrumental in setting up this Parisian institution. In 1995, Mitterrand wrote the preface to her book that recounts this experience with people at the end of their lives. From 1996 to 2002, she was qualifying in Jungian psychoanalysis and training in psychotherapy through hypnosis. Then in 2002 she was entrusted by the French health minister with researching and reporting on the issue of the end of life; that report helped secure a new law in 2005, detailing the rights of the sick and how the state should view the end of life. From 2005 to 2012 she was a member of the steering committee of the National Observatory on the End of Life and has since run seminars on the art of ageing well.

With such a wealth of professional experience behind her, it is odd that there is not more substantive detail in her book from that personal engagement. Instead the balance falls vey much towards the inclusion of the views of other authors in her cut and paste approach to writing. We also have a section where she shares the opinion of 'many of my colleagues who are psychotherapists ... that Alzheimer's disease is a progressive way to avoid confronting the approach of death.' She and they feel less inclined to value an explanation which accepts that such a disease is a neural event, not yet understood and so incurable, and usually associated with ageing. De Hennezel's approach here seems to lack rigour.

In the early part of her book she laments what she sees as a French malaise: a distaste for growing old and a fear of death. De Hennezel acknowledges that when she reached the age of 60 she began to feel that she had aged and that things would 'get worse'. She had had a painful divorce and a love affair which had ended in disappointment. She claims that the books she had read in preparation for writing her book gave a very bleak image of old age (pp.17-18). This opinion seems at odds with the views she has found and shared in much of the book. It is true that the book references a number of cases of neglect and abuse of the elderly but so many of the views of writers she cites are full of insight and wisdom regarding the potential for life in those who are ageing.

Such a dynamic and optimistic view of growing older does shape Marie de Hennezel's way of thinking about ageing - and that needs applauding. She tells a story from earlier in her life - would that there were more of these - when she was working as a psychologist at the bedsides of the dying:

'Her eyes (the eyes of a woman of 92 whom she was sitting with half an hour before her death) filled with fire and she gripped my hand and spoke: 'My child, don't be afraid of anything. Live! Live every bit of life that is given to you! For everything, everything is a gift from God'. (p.249) That is one of this book's authentic moments.

Another authentic moment is de Hennezel's account of the death of her mother-in-law aged 84 who decided that now the quality of her life seemed to be deserting her, she would take to her bed and stop taking food and wait for death. Her son supported her through the two months it took for her to die, and he arranged regular visits from the doctor and home-care nursing. De Hennezel comments: 'That is how I would like to die'; she also wrote a book about it called 'We Didn't Say Goodbye' (2000). Such an event needs much more unpacking then it gets in this 2008 book. De Hennezel is admiring an action that demands the support of others. Was her mother-in-law selfish? So much of the thrust of the second half of the book is towards a very different way of living and dying in which the ability to marvel at life is seen as one of the blessings of old age.

|

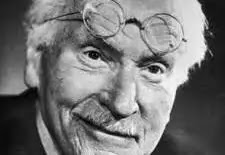

| Carl Jung |

There are a couple of times - (pp.149-151 and p.244) - when de Hennezel cites Carl Jung in support of her views but again the treatment is sketchy and does not do justice to the power and depth of his views. I will finish this blogpost by outlining the analysis of Jung's views on ageing offered by the psychotherapist, Isobel Clark, in a paper from 1992:

"Jung approaches the spiritual dimension of the person in a very different language from religious teaching; he is more interested in the deep emotional disturbances which stand in the way of the growth that is the given potential of every individual.

In religious teaching this would be called the journey to salvation. Jung called it individuation, the personal journey of each one of us towards our full psychic potential, the journey of the soul towards awareness. This journey tales place through the dark places of the psyche (what in religion is called 'evil', or 'sin') towards the integration of the rejected and repressed parts of ourselves that Jung called the shadow.

The goal is wholeness, and in Jung's mind it is by definition not attainable: the task is the journey, not the arrival...

Jung saw 'culture' as crucial to the path of individuation, 'culture' being 'everything that broadens the mind and uplifts the spirit' - art, music, beauty, relationship, philosophy, poetry etc. All these, and anything else that has meaning for the individual, are guides and companions on the journey of individuation.

The task of individuation fits into Jung's scheme of the stages of life as belonging to the second half and to old age. It comes to the fore when the tasks of youth have been achieved: status, separation, children, a place in the world. The person, freed of these, can begin the inner journey of the self to acquire the culture, wisdom and spiritual wealth brought by the process of individuation. For Jung, the approach of age is not a time to wind down but a point of new departure."

I think that passage on individuation above captures the essence of a fruitful approach to ageing. It also seems appropriate at this point to reference the epiphany moments of George Fox, the founder of the Quaker movement, who as a young man grasped the truth that we all have an inner self that is the seedbed of goodness. All humanity is equal in being blessed with this quality. Furthermore, although George Fox had no knowledge of the Gospel of Thomas hidden away in a jar at the edge of the north African desert, his 17th century mystical insights resonate so well with the teaching that Thomas the disciple identifies as coming from Jesus of Nazareth, his leader. Those teachings point to the existential importance of our inner self, too, as the Quaker, Hugh McGregor Ross, has explained:

- Something new is an emphatic theme of the Gospel of Thomas. Jesus's words are clear: he was presenting a new way of understanding Truth. This is in marked contrast to the Biblical Gospels that link the events and sayings of Jesus to quotations from the Old Testament. The continuity of Christianity with the Hebrew religion is a vital part of the Canon.

- The release from the Ego that both fuels us and blinds us is vital. Our ego can be contrasted with our real Self. Being egoistic or selfish, competitive and proud, depressed or fearful: all are manifestations of the ego. We need to transfer our attention from the ego that threatens to dominate us to the real Self so Truth becomes known.

- There is nothing in the Gospels of the Bible, coming directly from the living Jesus, to justify the extreme emphasis our Churches place on death and an after-life. By contrast, the Gospel of Thomas gives no suggestion that there is a continuation of life after death. Death in Thomas's Gospel is symbolic in character: in logion1, we read: And he said:/He who finds the inner meaning of these logia/will not taste death.'

- To avoid dying to the Truth even as we live out our life-span, we need to strip ourselves from the grip of a dominating Ego. Logion 4 captures the idea perfectly: 'Jesus said:/The man old in days will not hesitate/to ask a little child of seven days/about the Place of Life,/and he will live,/for many who are first shall become last/and they shall be a single One.' A baby is born without an ego - look at a baby of seven days, and you are looking at egolessness. That is perfection. That should be our aim. Jesus is clear: the baby is our exemplar, our competence model.

Interesting - I had my 70th birthday earlier this year and did feel it was a turning point though partly because I chose to make it into one. But I'm not buying that Alzeimer's (when did 'senile dementia' get relabelled by the way?) is some kind of unconscious choice. Brain scan show build-up of proteins and definite lacunae. It's surely a bit of a stretch to suggest that anyone's psyche would choose to create them, and the terrible anxieties and powerlessness they wreak - often for years on end

ReplyDeleteI am with you completely - I was shocked when I read that opinion. My mother-in-law was diagnosed with Alzheimer's and it was not a good ending. Here is an answer to your question:

Delete"In 1906, German physician Dr. Alois Alzheimer first described "a peculiar disease" — one of profound memory loss and microscopic brain changes — a disease we now know as Alzheimer's.

Today, Alzheimer's is at the forefront of biomedical research. Researchers are working to uncover as many aspects of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias as possible. Some of the most remarkable progress has shed light on how Alzheimer's affects the brain. The hope is this better understanding will lead to new treatments. Many potential approaches are currently under investigation worldwide."

But there is as yet no cure as we both know.

"Alzheimer's is the most common cause of dementia, a general term for memory loss and other cognitive abilities serious enough to interfere with daily life. Alzheimer's disease accounts for 60-80% of dementia cases."