Here is the text of my talk at the Penzance Literary Festival.

My gift to you.

|

| Delivered in the Penlee Coach House in the Morrab Gardens - image courtesy of the Festival team of photographers |

I hope you find the read worthwhile and stimulating.

Rob Donovan’s talk at The Coach House, Morrab Gardens,

Penzance on Thursday 7 July 2022, 3-4.30 pm

Good afternoon.

The theme of this talk is ‘The Power of Hope’ – what better day to deliver this talk than the very day that the man in No.10 resigns. I checked this morning on my website. I have written and published 171 political blogposts, nearly all of them critical of this very man. They start on the 14 December 2019, the day after the Tory triumph in the General Election. My blogpost then carries the title: ‘The resistance begins – still nailing Johnson.’. At the end of the blogpost, I provide a link to my previous blogpost, published on 11 December just before the election. That blog post carries

the title: ‘A question of intelligence – why Boris Johnson is unfit to be PM’. In it, I further reference the nailing of Johnson, this time in my first book: ‘The Road to Corbyn’, published in 2016. I have been on the case for a very long time.

|

| Copies now available from me, not Troubador! |

But back to my talk. Thank you very much for attending.

You make a writer very happy. I’m sure you are eager to hear – perhaps, dying

to know – how I’m going to make a case for the power of hope in our

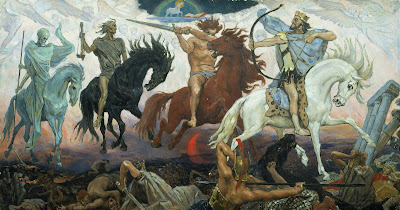

contemporary world. After all, this is a time when we are beset, as it were,

with our own four horsemen of the apocalypse.

The original four horsemen of the apocalypse entered the

head of a 1st century Christian visionary called John when he was in

exile on the Greek island of Patmos, and they feature in his book of Revelations

– the last book in the Christian bible. They represented conquest, war, famine,

and death. Louise, my wife, and I are drawn to the island of Patmos – eighteen

visits since 1988 – it’s a place of healing, despite those terrifying horsemen.

|

| The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse by Viktor Vasnetsov (1848-1926) |

But what of our contemporary four horsemen who threaten

to destroy any hopes we may hold dear?

First, we have a climate crisis that threatens the

existence of our species and so many other forms of life.

Secondly, we have a rising tide of inequalities in which

oligarchies and plutocracies flourish; a few, the very rich and their

institutions, seem to call most of the shots.

Thirdly, we still live under the clouds of a global

coronavirus pandemic that in this country alone has led to the death of nearly

200,000 citizens. There have been, according to the WHO, 6.34 million reported

deaths worldwide – and when you add the unreported deaths to that total you are

probably looking at around 10 million deaths so far in this pandemic.

And finally, we now have war in Europe, in Ukraine.

So – how do you make a case for the power of hope against

that backdrop? I hear the voice of doubt exclaiming: ‘Good luck with that one!’.

|

| Climate change collage |

And yet, I do. Hope really does spring eternal. We are

built for hope. We have an extraordinary capacity for living in hope.

Let me begin with a Prologue, an Overture. I want to

reference another writer’s very special literary achievement, a book that was

published in the UK in 2020. Here are some of the accolades it has received:

From the Daily Telegraph: ‘The book we need right now …

Might just make the world a kinder place’.

From the Times: ‘Filled with compelling tales of human

goodness … A thrilling read’.

From the Observer: ‘It makes such a welcome change to

read such a sustained and enjoyable tribute to our better natures’.

And from the Economist: ‘21st century readers

are short on prophets, especially the optimistic kind’.

Reviews to die for.

Who is the writer? He is a young Dutchman, born in 1988 – yes, 34 years young – an historian and author. His name is Rutger Bregman. His - I think seminal - work is called “Human kind – A Hopeful History”. My dear Dutch friend and reader, Ingrid Helmer, tells me that the Dutch version, published in 2019, is called – translating - “Most people are OK – A new history of humankind.”

|

| Rutger Bregman - from Wikipedia |

Mention of my dear Dutch friend and reader, Ingrid is a

prompt for me to deviate for a moment, but still very much within the focus on hope

for the future. Who are my readers, what do they do, and how did they become

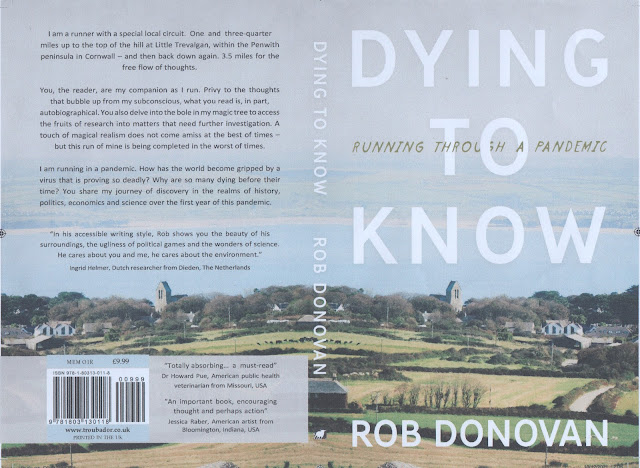

part of what I shall call my Band of Hope? The back cover of Dying to Know

tells you who they are. As for what they do, as I finished writing each chapter

they read and commented. The story of how they became my readers provides hope

for the future – it’s all about our increasing interconnectedness. My research

work on an English artist connected me to the American artist, Jessica. My

blogposts about the artist attracted the attention of a Dutch woman, Ingrid. Jessica

and Ingrid corresponded with both me and Louise, my wife. Jessica’ dad, Dr Howard

Pue, became my scientific and medical advisor. I relish this mutually

supporting, ever-expanding group of people, that surround me. In the research for

my next literary enterprise, MTD, I emailed an American organization called the

DiCamillo Companion who had the copyright on an early 19th century

engraving of Tehidy Hall, near Camborne. Out of the blue I got a response from

the boss himself – Curt – granting approval to use the image. Four or five

email exchanges later, Curt has now read Dying to Know and his last comment was

that the book gave him hope – the fact that reading my book gave this highly

successful and wealthy man hope – that felt very good.

So back to Rutger Bregman.

Bregman is an accomplished historian with brilliant

anthropological insights drawn from the most recent scientific research. He makes

the case that we are, as a species, an essentially cooperative being. Humans

have not evolved to fight and compete but to make friends and work together. It

is our unique ability to cooperate that helps explain our success as a species.

Homo sapiens flourished when the Neanderthals who were around at the same time

failed. Why? We enjoyed working together and that made us smarter.

Things started getting trickier when we moved from being

hunter-gatherers to farmers and began a new journey that has taken us from

villages to towns and cities, from simple communities to structured hierarchies

where power and wealth is concentrated in fewer and fewer hands. Bregman cites

the work of the anthropologist Brian Ferguson as representative of how anthropology

today views the origin of war. There is no convincing evidence for prehistoric

warfare. War has a beginning, and its origins are rooted in the acquisition of

power by the few who use force to maintain their grip and develop armies to

protect and extend their own territories. As Lord Acton brilliantly observed in

1887, “Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely”. Every time the

few who are in power resort to war or start reinforcing our defences, part of

our essential nature as a species withers on the vine. War and killing is not

good for us.

|

| R.Brian Ferguson - American anthropologist - born in 1951 |

In May 2020, Bregman wrote a piece for Time magazine in

which he quoted the words of the economist, Milton Friedman, in 1982:

‘Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real

change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas

that are lying around.’

I would add at this point, the wisdom of the late Frank

Musgrove, a remarkable professor of sociology at the University of Manchester, who

was one of my teachers for a year, nearly half-a-century ago. He said:

‘The health of a society lies at its margins. It’s there

you will find the ideas that can transform and save us.’

Back to Bregman and his ideas on the role of crises. He

claimed in that Time article two years ago that the economic impact of the COVID19

pandemic would underpin the biggest crisis the world has faced since the Second

World War – and that already the ideas that could produce real change for the

good were surfacing. He cited three: first, there were the ideas associated

with the then 17-year-old Greta Thunberg on the threat of climate catastrophe; then,

there were the ideas of the economist, Thomas Piketty, on the perils of

economic and social inequalities; and last, but not least, the ideas of Andrew

Yang on moving to a universal basic income. Remember, such ideas are out there,

at the margins – waiting to transform us and our society. In Wales, Mark

Drakeford’s Labour government has just launched a trial in which all those

leaving care receive an income of around £19,200 per year in line with the

living wage. We live in a world where we

can hope – and call it justified hope. There is light out there. It is very far

from being all gloom and doom.

|

| Rt Hon Mark Drakeford MS - First Minister of Wales |

For Bregman, the truth is that most people are not

selfish and egotistical. The notion that they are, has wormed its way into so many

people’s way of thinking – and yet there is plenty of evidence to prove it

false.

Still, Bregman acknowledges the scale of the challenge facing those of us with hope: Here’s an extract from his book (pp.240-1) that I can’t resist sharing with you because I think you will find it thought-provoking and tempt you to find names that fit:

‘Time and again we hope for better leaders, but all too

often those hopes are dashed. The reason, says Professor Dacher Keltner in ‘The

Power Paradox’, is that power causes people to lose the kindness and modesty

that got them elected, or they never possessed those sterling qualities in the

first place. In a hierarchically organised society, the Machiavellis are one

step ahead. They have the ultimate secret weapon to defeat their competition.

They’re shameless. We saw earlier that we evolved to

experience shame. There’s a reason for that, of all the species in the animal

kingdom, we’re one of the few that blush. For millennia, shaming was the surest

way to tame our leaders, and it can still work today. Shame is more effective than

rules and regulations or censure and coercion because people who feel shame

regulate themselves.

Unfortunately, there are always people who are unable to

feel shame, whether because they are drugged on power or are the small minority

who have socio-pathological traits. Such individuals wouldn’t last long in

nomadic tribes. They’d be cast out of the group and left to die alone. But in

our modern sprawling organisations, sociopaths seem to be a few steps ahead on

the career ladder. Studies show that between 4 and 8 per cent of CEOs have a

diagnosable sociopathy, compared to 1 per cent among the general population.

Shamelessness can be positively advantageous for a

politician. If they are not hindered by shame, they are free to do things

others wouldn’t dare. And their audacious behaviour can pay dividends in our

media shaped world which spotlights the abnormal and the absurd.’

Any names come to mind?

Bregman makes his own self-assessment, and it is one that

I identify with. ‘As a historian’, he says, ‘I can’t say I am optimistic, but I

am hopeful, because hope impels us to act. I am neither an optimist nor a

pessimist – I am a possibilist’.

I do like that. Hope makes good things possible.

So here I am – a possibilist, a guy who believes in the

power of hope. I am someone who has run through a pandemic and still emerged

alive. I can lay claim to be an exemplar of hope, triumphant. True, the clouds

of infection have not gone away; the crisis is still here, despite the official

attempts to ignore the virus in our midst. But I am protected by hope.

When I first had the idea of writing what became ‘Dying

to Know’, I was in the middle of a run. By now, as my wife and I approach the

tenth anniversary of our arrival in St Ives, I am used to thoughts bubbling up

from my sub-conscious during my local circuit run from home, up the Stennack

and then veering right along and upwards on the B3306, the coastal road to

Zennor and St Just. One and three-quarter miles of hill ascent and I reach the top

at Little Trevalgan, turn round, and have the joy of running back down the way

I came. Three and a half miles of exercise and free-thinking.

|

| The reviews are from my two official readers, Jessica and Ingrid, and my science and medical advisor, Howard |

Let me share some of the fruits of this free-thinking

with you. This is from the first chapter of Dying to Know as the book starts to

take shape and ideas from my inner core surface. My work necessarily becomes autobiographical

in places:

Read p2.

As a writer, I am shaped by influences that I cannot

fully understand. Let me give you a brushstroke impression of the magic cocktail

that makes me what I am – a man of hope. In my mid-thirties, I had, one summer’s

day, a gentle conversion experience that confirmed my existing humanist belief in

living life well. My hope was and is that when I die, I might leave this world

a better place for my existence. For most of the last forty years, I have

identified myself as someone in the Christian socialist tradition.

A few more brushstrokes, I think.

I don't believe in miracles; there will always be a natural explanation

of the seemingly supernatural. I don't believe we can know whether there is

life after death; it seems to me that the available evidence suggests that

there is not. I don't believe that prophecies from the past should shape the

way we live life today. I don't believe in the literal truth of the

resurrection story that was critical to the beliefs of the first Christians and

those that followed for so many centuries of Christian worship. I am a

demythologising Christian.

I am a man who believes in the provisional truths revealed by our human

pursuit of what we call science. I mistrust the certainties of those who claim

to know the truth of a revealed religion.

I do believe, though, as Hamlet said to Horatio, "that there are

more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy".

Whilst I trust that scientific research will reveal more about our human

nature, I sense that there are matters we may never fathom. Silence and awe can

be the most appropriate responses in the here and now. I find deep meaning in

the Hebrew belief that we are made in the image of God. When I was in my teens,

I relished the notion of the theologian Paul Tillich that Bishop

John Robinson made popular in his book 'Honest to God': God is the ground

of being, the ground of the structure of being. Like them, I distance myself

from the anthropomorphic idea of a personal God.

There. Enough brushstrokes for you to see that my belief in the power of

hope is deeply rooted in this world and in our being, not in supernatural

interventions.

I think it’s time to fast-forward to the ending of my run. Part of me

resists because it seems counter-intuitive to do so. I was brought up never to

read the end of a book before you reach it by dint of reading all the previous

pages. I am sure some of you were, too. But, on balance, I think it is the

right thing to do in the context of this talk. For one thing, my dad reappears.

I must say I didn’t expect that but as they say, ‘give me a child until the age

of seven, and I will give you the man’. Michael Apted, the maker of Seven-Up,

died as the book was ending, so he makes an appearance.

So too does my teddy bear, Peter Ted, but that is also a reappearance.

He made sure his photo is in the book - on p.71 if you’re interested. He’s a

smart creature, my bear. He minded when I went off to university without him

and sulked for half-a-decade on a shelf in the cupboard on the landing upstairs

before I came and rescued him. But he took the long view and waited. Finally,

in 2019, came his opportunity. My college gaudy at Catz – St Catherine’s

College, Oxford. We went together – and he’s got the photos to prove it.

|

| Rob, Peter Ted, and Mum - Lewisham - circa 1952 - as displayed on p.71 of 'Dying to Know' |

Who else is there in this pot pourri of an ending? Well, there’s Socrates and the psychoanalyst,

Erich Fromm. And a robin or two. They are all agents of hope, one way or

another:

Read from p143-148.

I brought the talk to a

close at this point, the last words of the book. Fifty minutes seemed enough. I

had planned to continue with this text and readings.

When I reread Dying to Know, I am struck by how much hope there is in a

book which at one level serves very well as a report into the hopeless handling

of the arrival of a global pandemic upon our shores. I delight in celebrating

Jacinda Ardern’s humane and civilised insistence that for New Zealand, a policy

of herd immunity, without a vaccine programme, was ‘unthinkable’. Where there

are politicians such as Jacinda Ardern, there is always hope.

I live in hope that those responsible for the kind of behaviour that Engels

in the 19th century called ‘social murder’ will be called to

account. But I’ll settle for a charge of ‘administrative malfeasance’ if it

provides the best route to justice and accountability.

I have a hope that my big idea will catch on – that we are all rather

wonderful people who are designed to love life and each other and in so doing

fulfil our own true nature.

I would like to close with extracts from a section of the book which

seems to me to be redolent with hope. In it, I play with the idea of the Great

Carbona as a metaphor and explore MMT. Time, I think, for some explanations.

First, the account of the Great Carbona:

Read p.122 (from bottom paragraph) – p.125

And now, an account of MMT:

Read p.126-129.

Enough – I hope you have found the talk stimulating. Time, I think, for

questions

----------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment